Science in Early Childhood Development classes

by on 02/08/2025 ...

Young children starting preschool have a sense of innocent wonder and curiosity about the world. Whether watching snails in an aquarium, blowing bubbles, using a flashlight to make shadows, or experimenting with objects to see what sinks or floats, the child is engaged in finding out how the world works. It is not an exaggeration to say that children are biologically prepared to learn about the world around them, just as they are biologically prepared to learn to walk and talk and interact with other people.

Science is everywhere

Because they are ready to learn about the everyday world, young children are highly engaged when they have the opportunity to explore. They create strong and enduring mental representations of what they have experienced in investigating the everyday world. They readily acquire vocabulary to describe and share these mental representations and the concepts that evolve from them. Children then rely on the mental representations as the basis for further learning and for higher order intellectual skills such as problem solving, hypothesis testing, and generalizing across situations.

While a child’s focus is on finding out how things in his environment work, his family and teachers may have a somewhat different goal. Research journals, education magazines, and the popular press are filled with reports about the importance of young children’s development of language and literacy skills. Children’s natural interests in science can be the foundation for developing these skills.

Science focused curriculum

Teachers may wonder how the basic language and literacy experiences are integrated into a science-focused curriculum. Researchers have found that children are most likely to learn language and literacy skills when they have opportunities to use these skills in authentic situations (e.g., Goodman 1984; Teale & Sulzby 1984). The problem-solving approach associated with scientific inquiry is rich in language. Teachers can support children as they acquire and practice increasingly sophisticated language skills. The group discussion may be completed in 5 minutes or may continue for as long as 45 minutes. Throughout this period, participants are involved in coherent, contingent conversation. Whether active contributors to the conversation or listeners, children gain important practice in how to maintain conversational coherence, switch and return to topics, use language to move between the past, present and future, and translate between linguistic and mental representations.

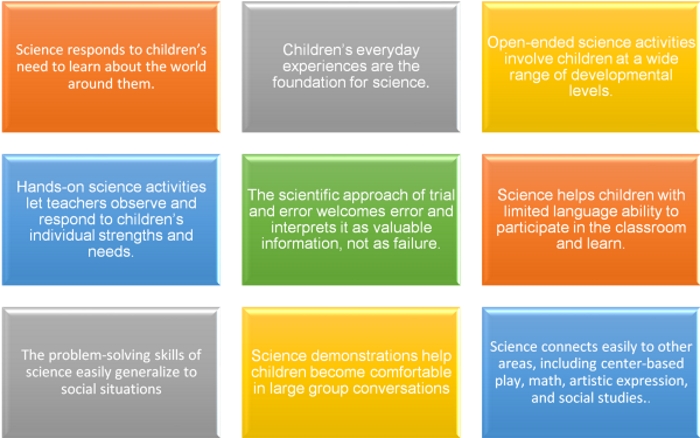

10 benefits of science in the Integrated Curriculum

Listed below are 10 benefits of Science at the centre of the Integrated Curriculum noted by Head Start Teachers:

Science strongly supports language and literacy

-

Nonfiction books become a powerful foundation for conversations with adults and peers

-

Vocabulary growth is supported by children’s prior knowledge and experience of the everyday world, coupled with observation and hands-on activities

-

Receptive language (listening comprehension) is fostered as children listen to the teacher read aloud and talk about the science activity

-

Expressive language is fostered as the teacher leads children through a cycle of scientific reasoning and especially as the teacher supports the children in developing a report of their findings

Teachers who increase their understanding of what science is at the preschool level will come to see that science can be incorporated into many, if not most, of the activities that they already do. Science itself is not an activity, but an approach to doing an activity. This approach involves a process of inquiry—theorizing, hands-on investigation, and discussion.

Workplace opportunities

With a steadily increasing number of STEM opportunities in the workplace, it is paramount that opportunities are not lost to engage children in the sciences. Early-childhood education is a perfect time to introduce future generations to the joys of scientific discovery. Addressing the lack of rich scientific discovery in primary schools is an excellent start at ensuring we have a full, diverse population of STEM innovators for the future.

Camille Thomson, who works on Australian Institute of Policy & Science’s Tall Poppy Campaign, a project to promote science in Australia, says there will be plenty of exciting and worthwhile jobs for kids who study science in the future.

“When we look at science and the discoveries that come through, we’ve only scratched the surface,” Camille says.

Jobs in renewable energies such as solar and hydropower are increasing rapidly. Then there is the conversation that goes with it in terms of preserving plants and animals.

“There is always going to be the study of different habitats as well as the increase in technology in renewable energies,” she says.

Medical research is also going to escalate. Even now, scientists are developing the ‘shoulders’ that future scientists will stand on in terms of cures for diseases.

Importantly, encouraging children to become interested in science can also result in a healthy dose of scepticism, Camille adds.

“It can teach kids to form their own opinions rather than take those of others for granted. In science you’re taught to go about getting a whole lot of information from different people and sources – experts, teachers – it’s not just Googling for the answer online,” she says.

“It’s about saying, ‘I’ve looked at a whole lot of things and made my own opinion’.”

10 scientific facts your child needs to know

1. |

Dinosaurs and cavemen did not live at the same time |

|

|

People did not coexist with the dinosaurs. Dinosaurs and people are well separated in terms of geologic time. Humans evolved about 65 million years after dinosaurs became extinct.

|

2. |

Batteries don’t have electricity inside them |

|

|

Chemical energy is stored in a battery; a chemical reaction converts the chemical energy to electricity. At the centre of each dry cell battery is a rod called a cathode, which is generally made of metal or graphite and is surrounded by an electrolyte paste. When a load is connected to the battery’s terminals, a chemical reaction occurs between the cathode and the paste in each cell to produce about 1.5 volts of electricity.

|

3. |

The Moon cannot only be seen at night |

|

|

The Moon can be seen in the daytime depending on its position relative to the Earth and the Sun. During the day, the Moon will appear white or grey because of the sunlight it reflects.

|

4. |

Rain doesn’t come from holes in clouds |

|

|

The clouds floating overhead contain water vapour and cloud droplets, which are small drops of condensed water. These droplets are too small to fall as rain, but they are large enough to be seen as clouds. Water is continually evaporating and condensing in the sky. The water droplets grow as a result of continued condensation and collision of the water particles. When enough collisions occur, they produce droplets and the droplets fall out of the cloud as rain.

|

5. |

The Sun doesn’t boil the sea to create water vapour |

|

|

Heat energy is used to break the bonds that hold water molecules together; water evaporates easily at the boiling point (100°C) but evaporates much slower at the freezing point (0°C). Water does not need to boil for evaporation to occur.

|

6. |

Objects don’t float in water because they’re lighter than water |

|

|

An object will float if it weighs the same as or less than the weight of the water it displaces.

|

7. |

Heat is energy |

|

|

Heat is a form of energy: the heat energy of a substance is determined by how active its atoms and molecules are. A hot object is one where the atoms and molecules are excited and show rapid movement. A cooler object’s molecules and atoms will be less excited and show less movement.

|

8. |

The Sun doesn’t disappear at night |

|

|

The Earth is a large sphere that is spinning. The Sun’s light shines on the Earth all the time; the side of the Earth that is facing the Sun will experience daylight. As the Earth keeps spinning, the side that was in the sunlight turns away from the Sun and enters the Earth’s shadow to experience night.

|

9. |

The Sun is a star |

|

|

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It has a diameter of about 1,392,000 kilometres – about 109 times that of the Earth.

|

10. |

The Sun is not smaller than the Earth |

|

|

The Sun appears smaller in size when seen from Earth because of the long distance between the Sun and the Earth. The radius of the Sun is actually 109 times larger than the Earth and the volume of the Sun is about 1,000,000 times that of Earth. |